What’s the Score? The role of the team in the festival community

Naomi Taylor is Creative Director at Chiltern Arts and a second-year PhD student at Birmingham City University. She holds a Collaborative Doctoral Award from Midlands4Cities for the project with the working title ‘Re-imagining the Arts Festival in Times of Crisis’, working in partnership with BAFA. Her research focusses on festival team dynamics, and considers changes within the sector since the Covid-19 pandemic. Chiltern Arts runs an annual Festival in May in venues across the Chilterns and is currently planning its seventh season.

A year and a half into my PhD research into festival teams, the most powerful message I’m currently taking away is that festivals are doing really essential work, in multiple ways. Our festivals present unique opportunities for audiences to interact with culture; many of us do the crucial job of creating and commissioning new work; our events provide joy and routine for a disparate community of individuals who may not feel they fit in elsewhere. And if we’re to continue doing this work, it’s important that we look inward and understand how it is we’re able to do that, what it is that makes this industry special, and the traits that we should focus on as we battle to keep our heads above water in these volatile, unpredictable times.[1]

Here I explore themes of community, belonging, language and imagination, and how important these are in the world of festivals and festival teams. While some communities are permanent features in our lives, others may be more temporary, or occasional — such as club membership, or attendance at an event. These short-lived or infrequent interactions have been dubbed ‘wispy communities,’ defined as “a distinctive form of local affiliation that underscores both the communal features of occasions and their evanescent quality.”[2]

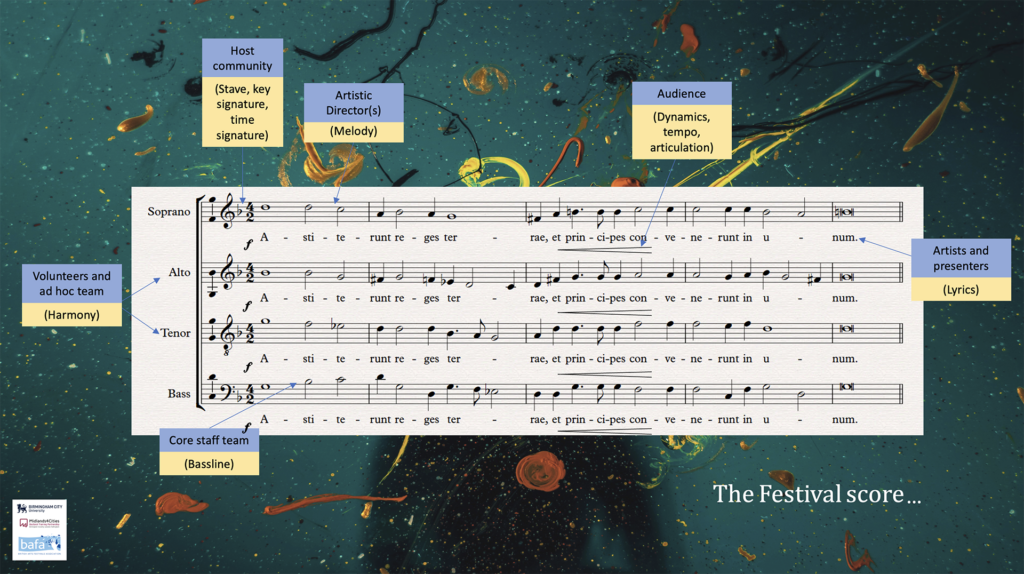

We find these ‘wispy communities’ all over the place — including, of course, at festivals. But festivals are complex things, and from the interviews that I have conducted so far, coupled with my own experience as a festival director and producer, it seems to me that festivals are made up of different layers of community. My background is in music — so when I tried to visualise these layers, the image that resonated with me was to see a festival as a piece of music, with all of the moving parts and communities within that festival making up the full score.

• Artistic directors = Melody. This is the festival’s USP.

• Core staff team = Bass line. Supporting the melody.

• Volunteers / ad hoc team = Harmony. Fleshing it out, bringing it together.

• Artists = Lyrics / Libretto. Context, variation.

• Audience = Tempo, dynamics, articulation. Bringing it all to life

• Existing community = stave, key, time signature. Giving the festival roots.

The ‘wispiest’ of these communities is the audience: they attend the festival, recognise friends from previous years and connect temporarily with locals. The artists are similar, dropping in simply for their events. But the directors, leaders and team members form a permanent community: these people live and breathe the festival for at least part of the year — and it is this which forms the bedrock upon which all the other ‘wispier’ communities are built.

When we align ourselves with a community — as opposed to society aligning us automatically — we choose to do so in order to effect a sense of belonging. That sense of belonging is a basic, human need: one of the most basic needs of all, and it’s the reason we try to conform and fit in. I’d like to explore now whether the sense of belonging at a festival may also begin in the team.

Festival teams are often small, and while some larger festivals have a number of office-based workers, many will have entire teams working from home for the majority of the year, and almost all festivals will have additional team members for the festival itself. During the festival, those teams find themselves in a situation where they are living in one another’s pockets for days or weeks at a time. As many team members in smaller festivals may have multiple freelance roles, managing their time accordingly, often this is only that period of time where the festival is the sole focus of all team members — resulting in a high-energy, intense atmosphere.

I ask my interviewees about the way they and their teammates view each other, and also what they love about their job and about festival time. Camaraderie, joy, adrenaline and ‘that buzz’ are all words and phrases that festival team members have used to describe the experience of festival time. People talk about supporting one another, believing in one another, and there is a real sense of caring. The sense of loyalty and respect for one another is tremendous. Comparing these answers to a Harvard Business Review summary of what it takes to create a sense of belonging at work, it is evident is that these team members feel seen, feel connected to others, will support one another, and are immensely proud of what they and their festival do.[3]

As my research continues, my interviews are beginning to focus more on looking at what characteristics those working in festivals may share, and why it might be that this sense of belonging is so prevalent in festival teams. The words calm, unflappable, practical, efficient and organised have all come up in these conversations. Also evident is the remarkable ability to simply see what needs doing and to do it: the unboxing of roles, which Liz Wiseman talks about in Impact Players.[4] Other traits that Wiseman recognises here include taking the initiative, pushing things over the finish line, learning as you go, and sharing the load. My research is showing me that impact players appear frequently in festival teams — and those who don’t fit that description tend to fall naturally by the wayside.

A pattern emerges: a team of individuals, who have consciously or otherwise nurtured a culture of belonging, who deeply respect their colleagues, whose particular skills allow them to create something with which others identify in a way that is so powerful they will plan their year around it. It is the task of the festival team to create and tame that beast with which people identify and the environment in which the wispy communities develop; and also to create the circumstances in which the anticipation is such that participants are able to look forward to the festival. But how?

“Vision” has been identified as “the single most important attribute for event managers” — because this “vision” (i.e. the use of imagination to visualise the form an event may take) allows the event manager not only to plan for and execute an event, but also to share that vision with potential attendees through a marketing strategy.[5] In the hefty volume Event Studies, events are described as “temporal phenomena, with start and end points, yet the experience of them begins before and possibly never ends!”.[6] For this to be the case, the whole team must have the ability to grasp and understand that vision — because for so much of the year, that vision is all that there is.

This requires the use of active imagination for both planners and participants. Philosopher Paul Ricoeur refers to reproductive and productive imagination.[7] The reproductive relies on memory, creating image from experience; and the productive relies on interpretation of language to “create new worlds”. Others observe that in order to feel that we belong somewhere, we must already feel in some way connected to or have knowledge of that place, event or community — i.e. we must assume a level of pre-understanding if we are to belong.[8]

Strengthening the identity of the festival year on year by creating a number of similar experiences will undoubtedly strengthen those “wispy” communities — and it may follow that this results in more memberships or donations, more word-of-mouth publicity and any number of other positive effects. However it also presents a challenge that calls into question potential issues of inclusivity and accessibility: how can we use language in such a way that new participants will be able to use their own productive imagination to consider attending an event of which they have potentially no pre-understanding? Language plays a crucial role in that sense of belonging, and it is so easy to exclude people by using language that is unfamiliar to them, or implies the need for a level of understanding that they do not feel they have.

And on this topic, I would like to just home in on one very specific word: festival.

The word is a powerful one: it immediately conjures up images for all of us. When we say “I work in festivals,” we see eyes light up — and simply being able to see the impact that the word has on people is remarkable. ‘Festival’ sounds like a celebration. Of course, it is rooted in celebration; in feasts, and in religious holidays… and I think it might just be possible that the word itself has an impact on how we all identify with our own particular involvement.

A much-quoted description of festivals is one proposed by Alessandro Falassi: a festival is “time out of time.”[9] As far as our collective experience of festivals goes, this could be understood as something internalised by each individual. While we immerse ourselves in a festival, we put on hold other things in our lives: the festival consumes our full attention span — or, as neuroscientist Dr Amishi Jha discusses in Peak Mind, our “flashlight” is on that festival.[10]

While this is a well-explored concept in terms of festival audiences, the idea that this is also experienced by team members has not been written about so extensively. The luxury to be able to have that total immersion is rare in modern life, particularly for periods that are as long and intense as a festival. It is perhaps this permission that we give ourselves to be fully consumed by the festival, to give ourselves over to those rhythms and patterns[11] of festival time, that creates such a strong feeling of camaraderie — which in turn, in an almost symbiotic way, strengthens these ‘wispy’ communities, inspiring our teams and strengthening the very foundations of the festival.

So — how could we use these observations in a practical way? Well, drawing inspiration from this article about curating festivals and how to adapt to today’s challenges, awareness is the best place to start. Being aware of how our teams interact, how they communicate, who and where our impact players are and understanding how those people integrate with each other and with the wider festival community might be a way to step back, think about things in a different light and perhaps gain a different perspective on something you know really, really well — which we can all benefit from sometimes.

Think back to the score image of the festival: if your melody is in a different key to your bass line… things don’t feel good. If your harmony isn’t quite working or your timing is off, it doesn’t matter how precise your dynamics are: no-one will hear them through the dissonance. Every layer works with and depends upon every other layer — and, as leaders, we have to be aware of all of those different layers and their particular quirks in order to make sure that the overriding collective and individual memory of that festival is the full score experience.

[1] Wickremasinghe, Nelisha. “It’s not my fault but it is my problem: The role of self compassion in a VUCA world.” The Dialogue Space Review. April 2017

[2] Fine, Gary Alan, van den Scott, Lisa-Jo. “Wispy Communities: Transient Gatherings and Imagine Micro-Communities.” American Behavioral Scientist 55, no. 10 (2011), 1319–133

[3] Kennedy, Julia Taylor, Jain-Link, Pooja. “What Does It Take to Build a Culture of Belonging?” Harvard Business Review. Published June 2021. Accessed October 6 2023, https://hbr.org/2021/06/what-does-it-take-to-build-a-culture-of-belonging

[4] Wiseman, Liz. Impact Players: How to Take the Lead, Play Bigger, and Multiply Your Impact. New York: HarperCollins, 2021. Summaries and resources also available online: “The 5 Practices of Impact Players”. Increase your influence, leadership and impact at work. Accessed November 27 2023, https://thewisemangroup.com/books/impact-players/[5] Brown, Steve, James, Jane. “Event design and management: ritual sacrifice?” in Festival and Events Management, ed. Ian Yeoman, Martin Robertson, Jane Ali-Knight, Siobahn Drummond & Una McMahon-Beattie (New York: Routledge, 2004), 55–64

[6] Getz, Donald and Page, Stephen J. Event Studies: Theory, Research and Policy for Planned Events, Fourth Edition. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2020, 56

[7] Ricoeur, Paul. “The Metaphorical Process as Cognition, Imagination, and Feeling.” Critical Inquiry 5, no. 1, Special Issue on Metaphor (Autumn, 1978), 143–159

[8] Kearney, Richard. “Exploring Imagination with Paul Ricœur,” in Stretching the Limits of Productive Imagination: Studies in Hermeneutics, Phenomenology, and Neo-Kantianism, ed. Saulius Geniusas (Rowman and Littlefield, 2018), 187–204

[9] Falassi, Alessandro. “Festival: Definition and morphology.” Time out of Time: Essays on the Festival 1 (1987)

[10] Jha, Dr Amishi P. Peak Mind. London: Piatkus, 2021

[11] Jamieson, Kirstie. “Edinburgh: The Festival Gaze and Its Boundaries”, Space & Culture 7, no. 1, (February 2004): 64–75

Festival Life creates shared moments of audiences and artists, eye-to-eye