Eternally owned is but what’s lost!

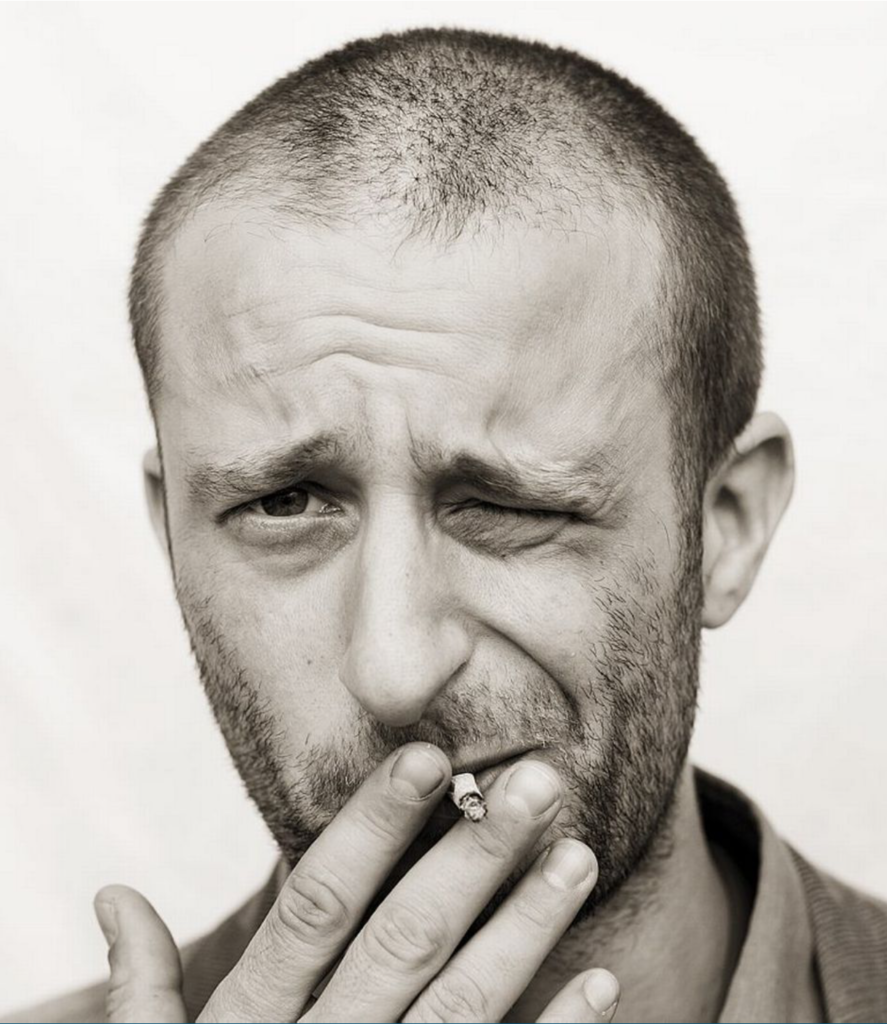

Jo Strømgren (1970) is a choreographer, theatre director and playwright from Norway. His 25 years of work covers about 200 productions representing a wide range of genres and styles, spanning from puppet theatre and ballet to opera and feature films. His theatre work has been focused on Henrik Ibsen and new drama, along with an extensive research on nonsensical languages. He is Associated Artist at the Norwegian Opera & Ballet and Artistic Director for his own independent theatre company. For further info: www.jskompani.no and www.jostromgren.com

I am writing this at the moment when 8000 people per day get infected from a disease that only nine months ago was unknown to us. I try really hard day in day out not to view our lives through the “before-and-after-Covid 19” perspective. It might be the right point of view at this moment, but for the sake of my mental wellbeing, I find it easier to keep my routine, avoid groups of people, wear a mask, disinfect my hands and wait for this to be over; the “one-day-this-will-all-be-over” approach used to save peoples’ lives in this region. I have already seen this “one day” several times in my life. The truth to tell, a better part of your life is also over in the meantime, but, sometimes, that is the only survival mechanism when you are surrounded by a chaos. The trouble with this most recent chaos is that it is like no other. Like everyone else, I had to improvise.

Ibsen put a lot of famous one-liners into the mouths of his characters. Brand got a fair share of these, perhaps due to his imperative manner of speaking and relentless quest to reveal the true nature of humans, things, and everything. This particular quote of his sounds indeed horrifying to contemporary consumer slaves, whether they glutton on culture or cars. But once you let it linger for a while, and leave out the religious connotations, it is in fact a rather soothing message. Good memories make you rich. More than earthly success.

As the festival world has come to a grinding halt and everyone, from bottom to top in the festival food chain, is wondering whether to focus on today or tomorrow, I would propose spending the rather indefinite waiting time to focus on yesterday instead. Some moments are perfect for evaluation and a paralysing pandemic is exactly that. We always spend the last days of December, that little void in time where nothing happens, thinking what really did matter that year and clearly understand what ought to matter for the next. Does the festival world take its time to do the same?

I can give a suggestion on how to start such a retrospective gaze. After having performed an average of 300 shows annually for 25 years in theatres and festivals around the world, in more than 60 countries to be specific, my question to myself is: which memories from all these festivals actually make me feel rich?

The obvious scrutiny for everyone in the food chain would be to look at the artistic successes, the impeccably executed programmes, the full houses, the good reviews, the perfect logistics, the break-even budgets, and so on. The list of “memorable” achievements is long. I cannot predict what people in different professions actually define as good memories, but from a visiting artist’s viewpoint, I can hereby present an absolute fact: a perfect festival experience is something artists may forget very quickly. A pleasant travel, nice hotel room, delicious breakfast, festival passes that leaves no questions, cheering audiences, civilised chats afterwards with sponsors and staff, reading a good review on the way to the airport again the next day. This is how it should be and what we all aim for, but the sad thing is that such experiences seem to simmer off into a haze after some time. Often into total oblivion. If you ask prolific artists with a high frequency of festival appearances whether they remember your particular festival, you may not like the answer. This is highly hypothetical though, as this is one of those situations where politeness ranks higher than honesty.

So, what do artists remember? The answer is simple and cruel: we remember everything that went wrong. Everything a festival strives to avoid is food for our eternally owned memories. It’s actually a fantastic message to all festival directors. When the catastrophe occurs and you are down on your knees or force a poor subordinated representative to kneel in your place, either in shame or apology, you can be sure that this is the start of a solid memory. Which is far better than no memory at all. Artists may be outraged, act like infants amid a tantrum, and swear never to come back. However, a few years later they will drink to it whenever they can and talk about how much they miss exactly such things: surprises, challenges, fear, improvisation, and well, actual stories to tell. There is no thrill hiking in the forest if you know there is zero percent chance of meeting a bear or a wolf. Or for countries who don’t host those, an angry wild boar. Risk is part of the artistic thrill.

Me myself, I am eternally happy for that festival where the green room sofa was full of fleas, from which I still have visible memories on my skin. I’m eternally happy for the festival where the elderly female director chased me like a sexual predator, giving me that experience of true fear which we so often miss out on in contemporary life. I’m happy for that sand floor stage the festival did not tell me about, which provided an important insight into the true nature of panic, likewise the festival that forgot to mention religious censorship until an hour before show opening. I thought I was quite creative before that, but now I know that new levels of creativity can be triggered by, for example, the threat of imprisonment. I’m eternally happy about the festival where the set design was split into two by chainsaw to fit transport. Although it was a rather neanderthal act, it was also a lesson about pragmatic thinking which we all could benefit from. It was also an effective incentive to evaluate how you treat festival staff and a reminder of being nice to absolutely everyone, just in case.

A valuable memory was also the festival where half the company got arrested by corrupt police. Not to mention the ransom price to get them free. The warmest memory was still that the festival staff turned off their phones when kind assistance was needed. Of the more grateful memories are those where festivals have booked a children’s show for an adult audience, and vice versa. But as always, you cannot be reminded enough of the charm of human error, even if you are the one to stand in that famous rain of tomatoes. Lesson learned there, too. I don’t say that the stage is the safest place anymore. It’s the wardrobe. As a last example, I could mention the festival where a local staff member was drunk at work. To cover up, he reported that we were the drunk ones. Despite the rather far-fetched paradox of performing a dance show drunk, the company suffered a reputational set back. A wonderful memory which has brought many good moments, especially when having drinks for real.

The list down memory lane could go on forever. On the other side, the haze-of-oblivion list from the perfect festivals is short. If anything, it’s unfair. So many people all over the world, from directors to volunteers, from marketing departments to sponsors, are involved with organizing festivals the best way possible. Trying to foresee whichever crisis or unfortunate incident, simulating the worst and working hard to achieve the best. But it may also be a relief to acknowledge that eternal ownership of something gone wrong is valued by the artists themselves. What’s lost in apparent failure is, in fact, not lost at all.

Festival Life creates shared moments of audiences and artists, eye-to-eye