Voice from Krakow

Berlin Conference 2020

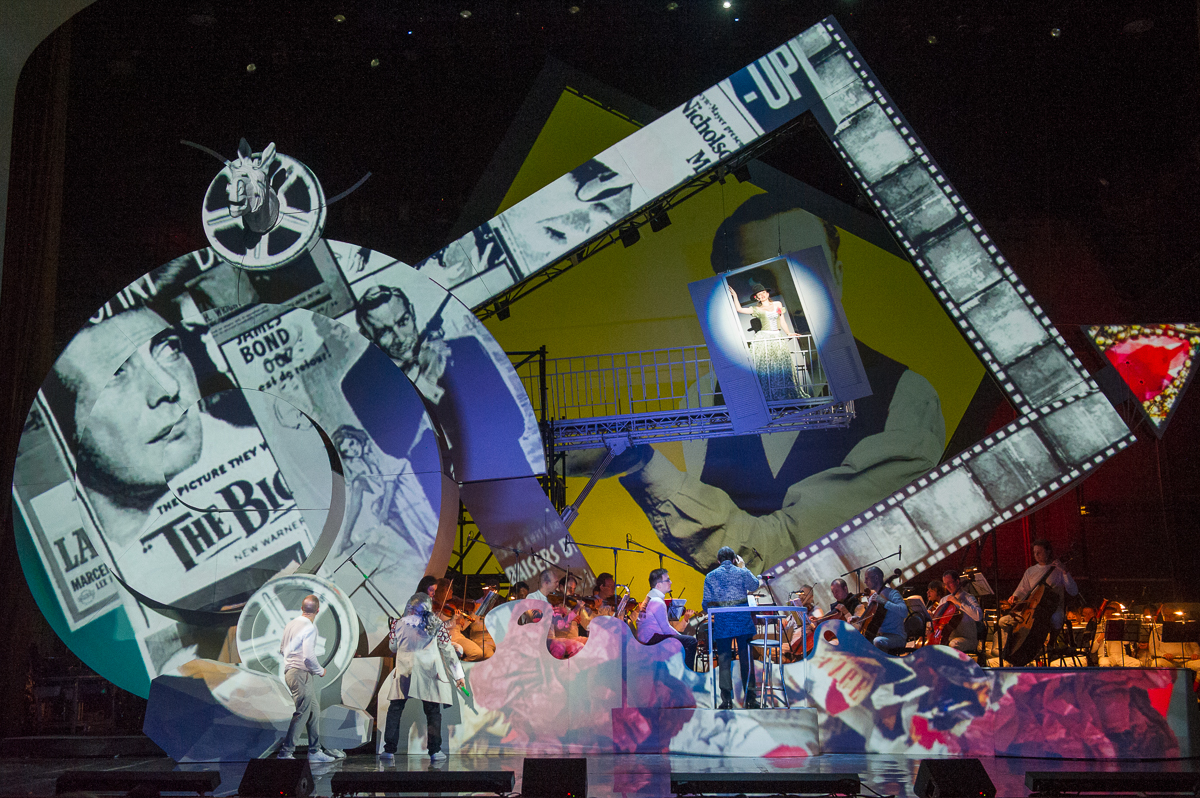

Robert Piaskowski is a cultural manager, animator, sociologist and diplomat. Since 2003, he is associated with the Krakow 2000, which was transformed into the Krakow Festival Office. He was responsible for the most important international festivals in Krakow, including Misteria Paschalia, Opera Rara, Sacrum Profanum, ICE Classic series, Conrad Festival and Miłosz Festival. He is the artistic director and co-founder of the FMF – Krakow Film Music Festival. He was responsible for the process of applying for the title of a UNESCO creative city of literature, also managing the activities of the Krakow Film Commission. Currently, he represents the Mayor of the City of Krakow as his Plenipotentiary for Culture. He lectures at the Jagiellonian University and at the AGH University of Science and Technology Kraków.

Like so much else these days, culture has reached a breakthrough point, if not a breaking point, for some critical areas.

Over the past decade, in particular, the rise of national populism, political propaganda, conspiracy theories and deliberate, systemic disinformation (accelerated by ultra-efficient global communication technologies and immediate access to online entertainment) has exposed critical weaknesses in the fundamental relationship between cultural decision-makers and real-life priorities for culture in today’s world, especially at the local level.

In other words, the gap between the top-down and the bottom-up (in culture) has grown too far apart. In some countries, especially those where culture budgets are influenced (if not driven) by a political agenda and ideological motivations, the implications are rather obvious.

The City of Kraków became the European City of Culture as early as 2000. 20 years later “culture” continues to be the single most important pillar of Kraków’s identity (however costly it may prove in the long run, both literally and figuratively). And so it shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that we strongly support the co-operation of several dozen entities working on the agenda aimed at forging a new vision for the role of culture within the EU.

(We, the) people representing the cultural sector, have long believed that culture is not a priority for the EU, and certainly not at the level needed to bring nation states closer together again, as a community of shared principles, values and rights.

Speaking of values, it was not COVID-19 that caused the rise of populism, nationalism, isolationism, and ultra-nationalism. But it has definitely become a powerful catalyst, exposing the huge challenges we are facing.

“Without the right language, Europe not only risks becoming too distant a concept for people to relate to and feel part of, but provides powerful arguments for populists.”

The rise of populism, isolationism, misogyny and homophobia is a painful reminder that even a notion as fundamental as diversity is a constant challenge for so many. On the positive side, the recent mass protests in Poland, joined by hundreds of thousands of our country’s citizens, in large cities and provinces alike, demanding fundamental rights for women and minorities, were one of the most fascinating examples of a festival of pro-European attitudes. In order to add fuel to its Euroscepticism agenda, Poland’s public television – entirely under the control of the central government – suggested that these protests are being financed by the EU.

Without spending too much time on specific examples, of which there are plenty, let me focus on a fundamental difference between nationalists and democratic leaders when it comes to culture: nationalists throughout Europe know very well how to use culture to trigger ‘cultural wars’ and strengthen their own power in the process. Democratic politicians, by contrast, from left to right, have long ignored or undermined culture as a means of bringing ‘cultural peace’ and bringing democracy out of the crisis.

Leaving culture entirely to the decisions of nation states has proved to be a catastrophic mistake in some countries.

In Poland and Hungary, for example, even the most progressive institutions are now beginning to censor themselves on fundamental issues such as the rights of women and minorities. They are afraid of losing state and EU funding.

I remember when, in the middle of a political campaign against LGBT minorities, one of the theatres in Krakow hung a rainbow flag on the facade. But only one. The other institutions did not want to provoke state anger. It was an important symbol. Recently, the Mayor of Krakow decided that some of the city’s public institutions would be illuminated in the colours of the rainbow as a sign of solidarity with the LBGT+ community. Two of them had major reservations, however, fearing they would lose state funding and sponsorship from state companies as a result. Under such circumstances, it is hardly surprising, perhaps, that the culture of tolerance is being contemptuously described by the leading pro-government media as ‘extreme leftism’ and ‘anti-Polishness’.

Distribution of funds in Poland is decided by bureaucracies dependent on local political distribution. Unfortunately, European funds are no exception, because they are distributed by:

a. State agencies, including funds channelled through the Ministry of Culture or the Ministry of Development. Defiant administrations, institutions and cities will most likely be denied access to these funds.

b. Regional agencies, but it should be clearly stressed that regions where representatives of the populist right-wing government have gained power are very difficult for cities to cooperate with. An example: the region of Małopolska, which surrounds Kraków, has declared itself an LGBT free zone. Krakow, in turn, ostentatiously and in response, adopted the opposite resolution, as a city that is clearly open to minorities. The ideological dispute between the city and regional authorities is not just a specific feature of Kraków.

The most important goal today is to “glue societies back together”.

A profound change in EU language is also unavoidable. Over the years, it has become too bureaucratic, generic, procedural and abstract, hence, increasingly distant and unrelatable. Today, above all, we need to reclaim a true sense of community in the way we talk about culture. Only then can we come closer to building a compelling case for a Europe-wide cultural vision. Without the right language, Europe not only risks becoming too distant a concept for people to relate to and feel part of, but provides powerful arguments for populists.

We should never forget that culture is first and foremost about creators, animators, educators: “artists in cities and little homelands”, and culture should never turn away from the greater solidarity with issues relevant to its immediate surroundings. We must return to the discussion on fundamental values. Values such as the rule of law, human rights, tolerance, democracy, freedom of speech and artistic expression. The most important goal today is to “glue societies back together”. Perhaps the EU should also have a new mechanism for promoting Europeanness, much like the network of the French Institute, the Goethe Institut or the British Council, a subtle network relying on soft influence by entering the structures of cultural diplomacy in individual countries, and at the same time becoming part of local cultural milieu.

During the time of the pandemic, we have all seen a new type of co-operation: sharing resources, spaces, institutions, freelancers, NGOs, and, last but not least, know-how. Such processes should be supported, among others, by creating and supporting common spaces. To give you but one example, in Krakow we have recently decided to create a brand new hub for festivals, creators and festival organisers. In the process, we have saved a Baroque Palace in Kraków’s Main Market Square from becoming yet another commercial facility. Our goal is to create a platform for co-operation between entities from different sectors. 30 entities will be part of the project. It’s fair to say it was an ad hoc decision, an outcome of the pandemic crisis. Such initiatives, however, should be prioritised over short-term projects. It should be possible to raise funds for such initiatives quickly and locally.

EU policies on culture have promoted co-operation between cities and their counterparts in other countries more than between cities and their own regions. The ironic result is that Krakow is now closer to Edinburgh or Porto than its surrounding regions, 10 km away from its borders. EU funding should be designed to break down isolationism and monadism and support the emergence of common spaces, hubs for culture and creativity. The most important work we must support is not work on projects and grants, but on building and strengthening connections.

This text was developed in the framework of the Berlin Conference 2020.

Festival Life creates shared moments of audiences and artists, eye-to-eye