To Dream Or Not To Dream?

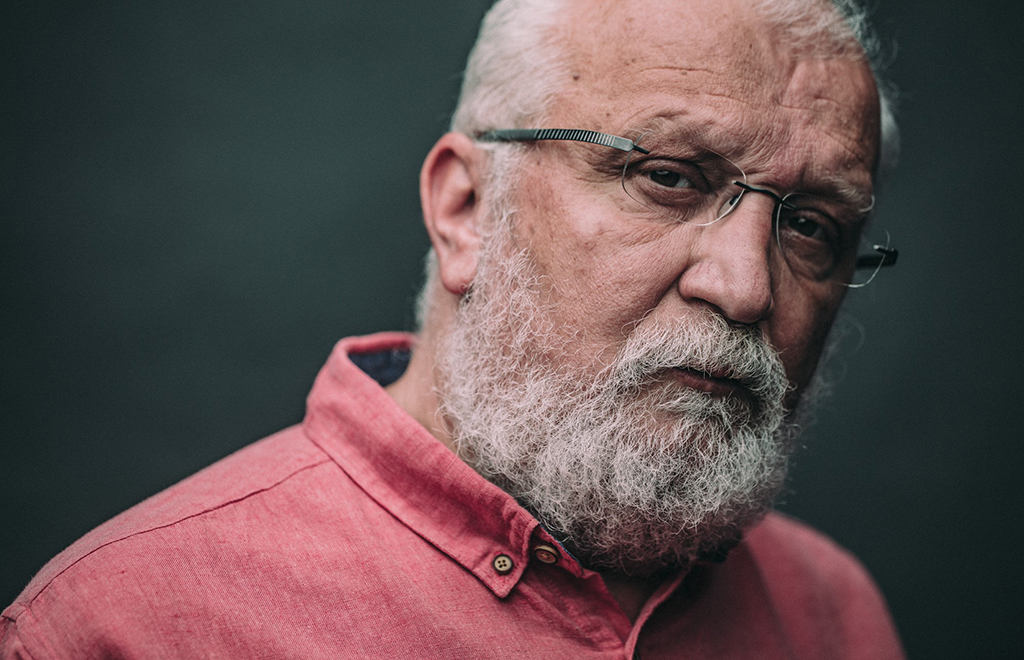

Haris Pašović is a multiple award-winning director. When Sarajevo fell under siege, he returned to the city. During this dramatic period he directed plays and also created the first Sarajevo Film Festival. He produced the now legendary Waiting for Godot, directed by Susan Sontag. His feature documentary Greta about Greta Ferušić, a survivor of the Auschwitz death camp and the Siege of Sarajevo, was shown at the New York Jewish Film Festival at the Lincoln Centre and other festivals around the world. Currently Pašović is Director of the East West Centre Sarajevo and the Artistic Director of Sarajevofest Art and Politics. Among other plays he has directed Hamlet; Faust; Class Enemy; Nora; Europe Today; Conquest of Happiness and most recently his own plays What Would You Give Your Life For? and Uncovering a Woman. Pašović also teaches at several universities.

It is devastating to watch the killing of people helplessly, the destruction and endless flow of refugees in Ukraine. Putin’s aggression is most brutal and furious. This war awakens my worst memories of the Bosnian war, which I survived, and the worst atrocities in Europe after WWII that happened in that war.

When I saw the Russian tanks rolling in and learned about the Ukrainians’ appeals for help, the first thing that came to my mind was: “Don’t, don’t, don’t live under this dream that the West is going to come and sort this problem out. Don’t dream the dreams!” These were – now historical – words told to the Sarajevans by Lord David Owen (see brief video), the British envoy who visited besieged Sarajevo in 1992, the city without running water, electricity, telephone lines and transportation and with only little food and barely some medicines; the city that was exposed to shelling and sniper fire around the clock. Hundreds of civilians including children had been killed and thousands injured by that time and the live broadcast of our misery was on prime-time news around the world. We were outraged by his words, but he was right. The EU and USA let us suffer and die for the four following years, even imposing an arms embargo on us. Only after the biggest atrocities in Europe after the WWII had been committed in Srebrenica did the USA and EU countries get involved and the war was stopped (though the peace has never arrived).

When the war in Bosnia broke out in 1992, I didn’t happen to be there. It took me a long time and difficult journey to come from Amsterdam via Ljubljana to besieged Sarajevo. I was a 30-year-old artist at the time and my role models had been for years Hemingway and Orwell in the Spanish Civil War; Ana Akhmatova during the siege of Leningrad; the Jewish artists of the Warsaw ghetto. I did have offers to work (and live) in Belgium, Netherlands and Sweden, but I could not imagine myself in any other place than in the city that was the very heart of resistance in the world – in besieged Sarajevo. Together with tens of artists in Sarajevo I was creating the arts. I created theatrical shows and managed the MES International Theatre Festival. I also established the Sarajevo Film Festival. It was all done under mortal attacks and inhuman living conditions.

I have the utmost admiration for Ukrainian artists who have stayed in order to produce culture and arts in these tragic times. We produced serious arts in besieged Sarajevo. Sometimes some of our friends who were the fighters in the defence trenches around the city visited us during our theatrical rehearsals. Once I asked them how did it look to them to come from the trenches to our rehearsal (of Alcestis by Euripides). Did they think that we were taking an easier way, that we were doing something unimportant perhaps? They answered me: “If you were not doing this, we would not have anything to defend.”

The international artistic solidarity was shy. There were a few artists who managed to come and work with us. It was so important for us to keep this international connection alive. That was also important for some of our international colleagues. Our voice meant something to them too.

During the war in Bosnia we never cut the ties with our colleagues in Serbia, the Serbian artists and cultural operators, nor our colleagues from Croatia, despite the fact that both countries took part in the invasion of Bosnia.

Several years ago I was asked by the International Writers Program of the University of Iowa to write an essay about my experience in the besieged Sarajevo: City The Engaged. I did not imagine that it could have been sent to someone in an actual war during my lifetime. Perhaps it might have some value for you…

“On a summer day in 1993, I went to visit the National Library. It was dangerous to get there. Its entrance was exposed to Mt. Trebević from where it could have been targeted at any moment. I knew I could be seen quite clearly from the mountain above. But I took the risk. I don’t know why. Risking my life to enter into a ruin? But I somehow had to do it. The entrance was partly buried under a heap of rubble, charred paper scattered all over the place. I took a piece – it was an old train timetable. I don’t remember which. I got through to the main hall. Once there, I was shocked. Terrified. Petrified. The building had been built in the pseudo‐Moorish style during the era of the Austro‐Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its main hall was under a glass dome and the rays of light used to hit its marble pillars, its balconies with their stone‐lace balustrades, its arches of various sizes and its shadowy lodges, from where dark corridors led in different directions. It all added up to a mystery, an exciting labyrinth. The very thought that somewhere in the interior of this monumental edifice there were millions of books, documents and manuscripts, gave the experience of entering into this library an almost mythical sense. Now I was standing in the midst of this ruin, looking at the melted marble pillars. The burnt books had melted stone! I was standing there. Lonely. Helpless. For a moment, I was the last man in the world.”

I believe that all of us experience the current aggression against Ukraine personally and some of us are thrown back to the very core of war, to the heart of darkness. Exactly because of that, I ask that we all find wisdom, to do the best we can. I am sure that a cultural boycott is not the best we can do.

All of us personally know colleagues in Russia, some of us have friends in Russian arts. They are not responsible for the war. Neither are our colleagues from the Russian arts festivals. I am afraid that the current massive call to boycott artists and artistic institutions from beyond Russia’s borders is persecution. What is next? To ask European artists to divorce if they happen to have Russian spouses?!

No European institution, organisation or association asked to boycott British artists when the United Kingdom invaded Iraq on a false pretext; nobody cancelled American artists because of Guantanamo Bay; we don’t expel Turkish colleagues because of the massive imprisonment of artists and other thinkers in their country. Of course, we haven’t gone after our fellow artists and cultural operators in those situations. Of course not! Because they have not been responsible in any way. Our dismissal would have made their horrible position in their countries even worse. At the same time, we would not help the cause by turning against our colleagues. Even during the worst time of the Siege of Sarajevo and the war in Bosnia, we did not cut the ties with our colleagues in Serbia.

There have been also other calls in public in recent days to force our colleagues in Russia to condemn publicly the politics of their president and government. I wish we were all courageous like we ask them to be. Also, are we ready to offer them and their families the jobs and shelter if they condemn their government and flee to Europe?

We are all frustrated with our marginal position in this tragic and urgent time. We all want to stop the war and help the Ukrainian people. Let’s try to find some practical ways to do perhaps little but concretely helpful things. We are insignificant in world affairs. But we can do something. Something useful. I am sure that a cultural boycott is not useful. It is maybe a feel-good action for a day, but already tomorrow, it does nothing but inflict more pain.

The war does not have to last for a long time. It is not a natural disaster. It is controllable. It is man made. It can be stopped. Any time.

Festival Life creates shared moments of audiences and artists, eye-to-eye